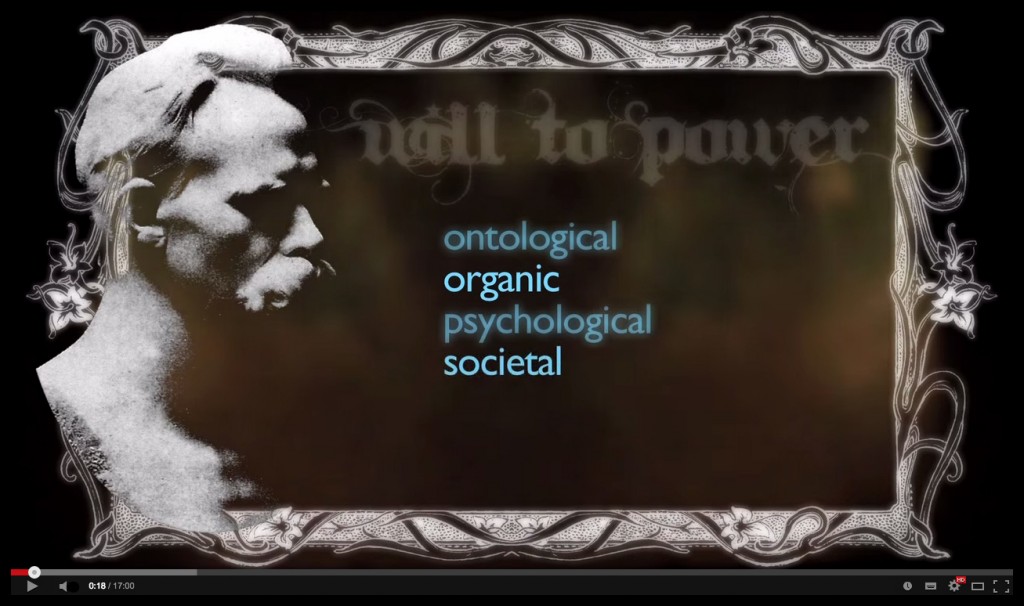

The Metaphysical Doctrine of Nietzsche’s Will to Power

Critique of Maudemarie Clark’s Position

– Peter Sjöstedt-H –

The view here advocated, the traditional view, is that Nietzsche contends all ‘matter’ to be ultimately force (Kraft), and all force to be the outer representation of an inner affect: the will to power (Wille zur Macht). As this immanent aspect to all force cannot be understood solely as physical, the doctrine is thus metaphysical.

It is maintained that this metaphysical doctrine was not completed due to Nietzsche’s cognitive ruination in 1889.

In 1990 the Nietzsche scholar Maudemarie Clark published Nietzsche – Truth and Philosophy, wherein she argued against this traditional interpretation of Nietzsche’s will to power as a metaphysical doctrine (chapter here) – a denial that triggered a considerable following. We shall here present criticism of her main arguments, a criticism that seeks to maintain the metaphysical, or cosmological, standing of Nietzsche’s central tenet, in defiance of Clark’s legacy.

Clark’s initial move is to say that we should ignore the passages on the will to power from Nietzsche’s notebooks because they were unpublished, and so look at the published works, with special attention to Beyond Good and Evil (BGE) §36. Then, with regard to this pivotal section, she argues that Nietzsche is not advocating a metaphysical doctrine of the will to power, despite appearances to the contrary, but is in fact putting forward a thesis which he does not believe to be the case. She argues that Nietzsche is playing with the reader, putting on a mask in line with his criticisms of other philosophical doctrines as nothing but mere memoirs of their authors’ characters.

The first cause for concern is Clark’s dismissive attitude to the notebooks of 1883-88, commonly known as the Nachlass. As Nietzsche was developing his doctrine of the will to power – as the proposed name of his never-completed book indicated (see his Genealogy, T3, §27, and below) – then that development would only be found in his late notebooks. Furthermore, the notion that the posthumous notes on the will to power principle were his sister’s fabrications is highly implausible (see here). Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche was no philosopher. According to Friedrich Nietzsche’s friend Peter Gast (Heinrich Közelitz) – the man who suggested to Elisabeth in 1893 the publication of Friedrich’s notes, and who transcribed those notes – Elisabeth could barely understand Nietzsche’s thinking, let alone could she contribute tens of passages on metaphysics. Elisabeth’s employee at the Nietzsche Archive, none other than Rudolf Steiner, held the same dismissive views.

The further importance of the Nachlass is implied in a letter to another of Nietzsche’s friends, Franz Overbeck (who never allowed Nietzsche’s sister to acquire his letters). In this correspondence dated 7th April 1884, Nietzsche writes:

‘If I get to Sils Maria this summer I want to undertake a revision of my metaphysical and my epistemological views. …

I am resolved to devote the next five years to the construction of my “philosophy,” for which I have in my Zarathustra constructed a vestibule.’

Nietzsche here explicitly indicates his desire to revise his metaphysics, which considered from 1884 and the more Naturalist philosophy of his mid-period, suggests a move away from Naturalism (physics, mechanism). He also refers to his book Thus Spake Zarathustra as being a mere ‘vestibule’ to his revised forthcoming “philosophy”. BGE was published in 1886 and so suggests that the ‘five years’ of the development of his philosophy were not exhausted in that book. Hence more reason to consult the developing thought within his notebooks.

Moreover the Nachlass contains more than a hundred sections on the will to power principle. This lights untenable Clark’s claim that BGE§36 was nothing but a trivial masked game for his readers.

Secondly, Clark’s anti-metaphysical interpretation is at odds with comments within his published works. In his autobiography, Ecce Homo (1888), Nietzsche describes BGE thus:

‘This book (1886) is in all essentials a critique of modernity, the modern sciences … All the things of which the age is proud are felt … almost as bad manners, for example its celebrated “objectivity” … its “scientificality”.’

Ecce Homo here obviously presents Nietzsche’s aversion to Scientism and, by implication, his embrace of metaphysical possibility – thereby annulling Clark’s mission. When Nietzsche attacks metaphysics in his mature work, he attacks specific doctrines rather than metaphysics per se. This distinction Clark conflates.

Thirdly, it seems that Clark also conflates ‘will’ with ‘free will’. The latter meaning that consciousness originates actions, the former, for Nietzsche, means a non-conscious yet affective striving underlying all force. Clark confuses this critical distinction when she writes, ‘[t]he ultimate causes of our actions, then, are not the conscious thoughts and feelings with which Nietzsche claims we identify the will. Given these passages [BGE§§3, 19], we cannot reasonably attribute to Nietzsche the argument of BG 36’. But BGE§36 does not argue that the immanent aspect of will to power is the consciousness that originates actions (free will), so the attribution can be made without incoherence to previous passages in BGE. In BGE§21, Nietzsche writes:

‘Now, if someone can see through the cloddish simplicity of this famous “free will” and eliminate it from his mind, I would then ask him to take his “enlightenment” a step further and likewise eliminate … “unfree will” … in conformity with the prevalent mechanistic foolishness that pushes and tugs … The “unfree will” is mythology: in real life it is only a matter of strong and weak wills.’

That is, free will and mechanistic determinism are both errors. Consciousness does not originate actions, and the mechanism in physics does not sufficiently explain reality. In reality there are a multiplicity of wills to power, their differing strength determining action – a non-mechanistic determination. In the Nachlass, Nietzsche words this in the following manner:

‘…no things remain but only dynamic quanta, in a relation of tension to all other dynamic quanta: their essence lies in their relation to all other quanta, in their “effect” upon the same.

The will to power not a being, not a becoming, but a pathos – the most elemental fact from which a becoming and effecting first emerge.’ (WP§635, March-June 1888)

This section was written in 1888 and thus offers a view on the development of his power project. As it reveals, the will to power underlies all actions and involves a ‘pathos’: a feeling. That Clark can deny this metaphysical aspect of the will to power is unjustifiable revisionism.

Clark writes, ‘Nietzsche encourages us to continue to think in causal terms … but to abandon the interpretation of causality we derive from our experience of willing. BG 36 therefore gives us no reason to retain belief in the causality of the will, nor any way of reconciling its argument with Nietzsche’s repeated rejection of that causality.’ But again, Nietzsche’s argument in BGE§36 does not involve causality of the will in this Libertarian sense. The will is not of necessity connected to the conscious “I” that believes it controls; the will is mostly subconscious, but it is nonetheless an immanent sentience underlying all energy. It is thus a metaphysical principle, as Nietzsche repeatedly makes clear.

Again, the Nachlass provides elaboration of Nietzsche’s thinking here. He writes in March-June 1888,

‘… the will to power is the primitive form of affect [Affekt-Form] … all driving force is will to power, that there is no other physical, dynamic or psychic force except this.’ (WP§688)

This passage alone hammers Clark’s argument. When she writes, ‘[t]he problem is that if willing is not conscious, it becomes impossible to understand how BG 36 would support its first premise: that only willing is “given,” and that we cannot get up or down to any world beyond our drives’, she betrays the fact that she does not distinguish consciousness from affect. The experience of will is not of necessity consciousness; shades of differentiation of sentience must be fathomed here.

Furthermore, from the Nachlass in 1885:

‘There is absolutely no other kind of causality than that of will upon will. Not explained mechanistically.’ (WP§658)

This obviously refutes Clark’s statement above regarding Nietzsche’s repeated rejection of the causality experienced in will. This experience is, as such, a posteriori, contrary to her initial claims that Nietzsche’s argument for a metaphysical will to power would have to be conditioned on an a priori basis. It is not.

In sum, Nietzsche’s argument against free will does not refute his argument that the will to power has an intrinsic aspect, which is causality understood from the inside – somewhat analogous to A. N. Whitehead’s cosmology. BGE§36 is not a trick.

Fourthly, Clark attempts to make the case that the proposal within BGE§36 of the will to power as metaphysical, or cosmological, would be a contravention of his Perspectivism. What she does not consider, however, is the fact that Nietzsche’s Perspectivism is grounded in his notion of the will to power: all perspectives are based on (mostly subconscious) considerations of power. She has inverted Nietzsche’s epistemic hierarchy, and in so doing has exposed his Perspectivism to groundlessness. Perspectivism cannot be applied to its own conditions without destruction.

The overall push of Clark’s theory, then, is to dethrone the will to power as a metaphysical and as a central tenet of Nietzsche’s philosophy, and to see it as a mere derivative part of his philosophy. She states, ‘the will to power, [is] a second-order drive that he recognizes as dependent for its existence on other drives, but which he generalizes and glorifies in his picture of life as will to power. The knowledge Nietzsche claims of the will to power belongs to psychology rather than to metaphysics or cosmology.’ Nietzsche directly contradicts this in BGE§23: ‘Until now, all psychology has been brought to a stop by moral prejudices and fears: it has not dared to plumb these depths … no-one in his thoughts has even brushed these depths as I have, as a morphology and evolutionary theory of the will to power.‘ Further, if the will to power was a mere psychological second-order drive, Nietzsche would not announce in his published Genealogy of Morality of 1887 that, ‘I am preparing: The Will to Power, Attempt at a Revaluation of All Values’ (T3, §27). Why would Nietzsche name the culmination of his thought from the time of his letter to Overbeck, with the name of a mere second-order drive? It is far more plausible that the will to power was conceived by Nietzsche as a central cosmological, metaphysical principle, as sincerely sketched in BGE§36.

Clark and her ilk would like to reject a metaphysical interpretation of Nietzsche’s mature thought for an empirical one. For instance, she claims that ‘Nietzsche’s doctrine of the will to power must be empirical if it is to cohere with his rejection of metaphysics’. But Nietzsche does not reject metaphysics as a whole in his mature work; he returns to metaphysics. Apart from the published texts and Nachlass, the error of Clark’s view is further shown in writings by Nietzsche’s friends who would have known his sincere philosophy from more than his books. One particularly close acquaintance was Lou Salomé, to whom Nietzsche proposed. In her book Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, she writes,

‘we can trace the transitions from his positivistic [empiricist] phase of intellectuality to a mystical philosophy of will … Nietzsche’s renewed glorification of the artist, and metaphysics even, tells us how far he has turned towards a new and opposite type of seeker and how far he has already distanced himself from the positivistic “reality-philosophy babblers” … Nietzsche’s theory of the will points to a merging of his former metaphysical views … as a disciple of Schopenhauer’.

Salomé’s book was published in 1894 and so presents an intimate understanding of Nietzsche’s proposed metaphysical character of the will to power, an understanding that predates Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche’s publication of the Nachlass, as well as the secondary literature by Alfred Bäumler, Heidegger, et al. (to which an empiricist revisionism can be perceived as counteraction).

I would argue, however, that this power principle was not fully developed by the time of Nietzsche’s collapse in 1889, which explains the somewhat cautious, conditional style of BGE§36. That caution is not present in the Nachlass, and it is mostly there where we find his most advanced thought. In a later letter to Franz Overbeck dated 24th March 1887, the year after BGE’s publication, Nietzsche writes,

‘there is the hundredweight of this need pressing upon me – to create a coherent structure of thought during the next five years’.

It is this acknowledged incompletion which bequeaths the hypothetical manner of BGE§36, rather than its insincerity, as Clark believes.

More generally, the question as to how Nietzsche himself conceived the will to power is not as important as the question as to whether it approaches a correct understanding of reality, if such an approach is possible. I believe this potential is hindered by Clark’s unjustified critique, and further impeded by those following her dismissal. This dismissal of Nietzsche’s cosmological will to power is itself, one could argue, a symptom of a structure assimilating and exploiting its environment for its own power: ‘the will to power interprets … interpretation is itself a means of becoming master’. (WP§643, 1885-1886)

‘The victorious concept “force” … still needs to be completed: an inner will must be ascribed to it, which I designate as “will to power,” i.e., as an insatiable desire to manifest power; or as the employment and exercise of power, as a creative drive …

one is obliged to understand all motion, all “appearances,” all “laws,” only as symptoms of an inner event.’ (WP§618, 1885)

©MMXV